For the past few years, I’ve set a yearly writing goal for myself with a specific challenge based on what I thought I needed to work on the most. Here are prior year’s goal trackers: 2020, 2021, 2022. January is upon me yet again and I’ve decided what I’d like to work on this year and that’s to write smarter.

2023 WRITING GOAL:

Write smarter: develop a better process that will allow me to finish books faster.

This is a many-sided challenge because several concepts come into play:

- Writing craft. I’ve been diligently studying the writing craft and I’ve learned a ton but I don’t always know how to put into practice what I’ve learned. If I really followed all advice that I think I follow, I would be finishing my books right the first time around and not a couple of years later.

- Choosing a project. I have several projects at various stages of completion. I may also be tempted to start new ones. I can’t work on them all at the same time, clearly, and choosing to work on one means I’m not working on another. There’s an opportunity cost to this decision.

- Writing process. So far, I’ve been pretty flexible, adjusting my writing process as I saw fit. I’d like to focus more on results right now and pay attention to what parts of my process actually work/help me and what parts don’t.

Quick jump to an update:

- January 2023: Where did I go wrong with this novella?

- Lesson 1: Innovating ideas

- Lesson 2: What not to do: distractions vs hobbies vs productivity

- Lesson 3: Flexibility isn’t evil

- Lesson 4 and 5: Understanding what is an audience and Connecting the dots

- Lesson 6: Choose the right tool for the job

- Back to Lesson 5: What connecting the dots actually is

- Lesson 7. A sense of mystery

January 2023: Where did I go wrong with this novella?

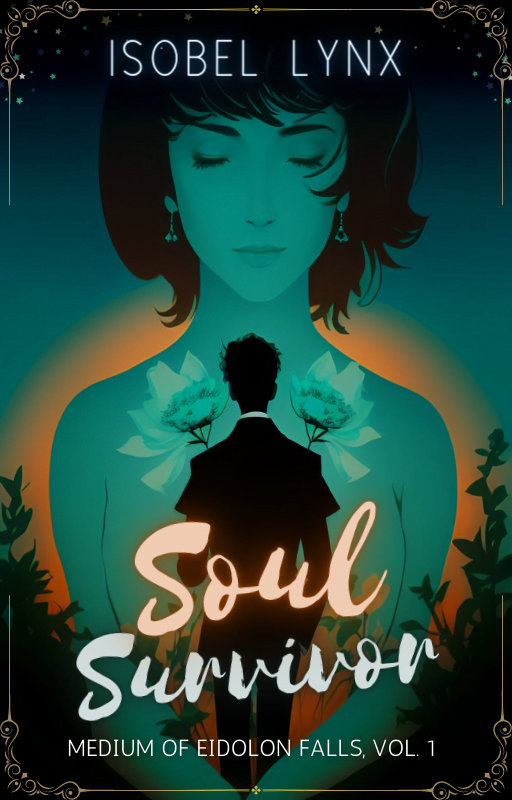

I have recently cracked the secret to fixing my novella, Soul Survivor of Medium of Eidolon Falls series, and it really annoys me that it took me two years to figure out how to save this story. I can’t believe I almost scrapped it completely when the solution to what was bothering me about it was right in front of me. If I had thought of it earlier, the novella would’ve done better in the contest, but even more importantly, a working draft would’ve been completed within three months. That is exactly the type of speed I’d love to be able to churn out books in.

After I’m done with the edit, I need to look at it closer and see where exactly I went wrong the first time around, and what blinded me to this solution when I tried to edit it later. I’d like to learn from this experience so that I don’t make this mistake over and over again.

Lesson 1: Innovating ideas

As I’ve tackled rewriting the climax of this story, I fell into a similar trap that I’ve fallen into the first time I was working on it: unsatisfying climax. I hated it even more than the initial ending I was trying to fix. After some brainstorming, I figured it out, generating a series of scenes I’m excited about and cleared the block that was preventing me from moving on.

THE PROBLEM was hiding in uninteresting execution. What started as an exciting climax, fizzled out and came to a plateau before the cathartic core moment of choice. Something was fundamentally wrong about the structure of the climax.

THE SOLUTION was hiding in an option I had not considered, an option which was an easy progression of events, a consequence to the protagonist trying to cheat and solve his problem the easy way. This consequence raises the stakes and makes sense with the established rules of the universe. It feels utterly silly that I hadn’t thought of this option before, that I had gone to such great lengths to get around the problem by adding more story on top of it when the answer wasn’t “more” but “different.”

THE MISTAKE I made the first time around was that I didn’t recognize in which moment I had messed up. I had started the climactic moment and allowed it to fizzle out, and then I tried to make up for it by adding another climactic moment later (which inevitably created a subplot at the last minute = bad idea). I should have spent more time brainstorming how to fix the moment when the climax fizzles out. I had given up too early. I had misdiagnosed the problem.

And so the lesson learned is ultimately to innovate more. This reminded me of advice Shawn Coyne has given Tim Grahl once upon a time.

Don’t use the first idea that comes to mind. Don’t even use the first ten. Those first obvious choices are how cliches are born because even if you can’t remember where you’ve encountered them, the first ten ideas are repetitions of what you’ve already seen/heard/read.

Shawn Coyne (paraphrased)

When I first heard Shawn say this, I agreed with it, but it’s been difficult to put this advice into practice, or even more so it was difficult to see when I didn’t put it into practice, when I’ve chosen the easy “one of the first ten ideas” approach.

Recommended reading

While I don’t remember which podcast episode I heard this advice on, this Story Grid article explains and expands on this idea with practical exercises.

I decided to add the “trust yourself” clause to my new process because it’s important to curb in the eternal conflict of perfection vs reality. I’m a perfectionist by nature which means that I’m never 100% satisfied, I always see room for improvement, and this can be a dangerous mindset to have in creative pursuits. So I’m constantly trying to loosen the leash and allow myself flexibility. I constantly remind myself that it’s okay if it isn’t perfect.

But in this case, my initial negative reaction toward the scene I had written was useful. My disappointment with it didn’t stem from perfectionism but rather from the desire to enjoy my own work. Fun fact: I am the perfect target audience for my books. I need to trust myself more when something does and doesn’t feel right.

New essential process: Recognize when the core moments are unsatisfactory and innovate the scene idea. Do not settle for “good enough.” Trust yourself when you feel that it’s not good, and challenge yourself to innovate the idea until you land on one that excites you.

Lesson 2: What not to do: distractions vs hobbies vs productivity

Now, this shouldn’t come as a surprise, but distractions are bad for your productivity. While I know that already, it’s easy to not notice when I diverge from activities that would help me make progress in my projects and spend it all on fun.

My recent distractions have come from other interests and activities. I don’t want to cut everything else from my life because it’s important to have things that make you happy, but I need to learn to catch myself when I spend too much time on them.

I saw a cool piece of advice today originating from Neil Gaiman and that’s to dedicate time to write, and during that time, you don’t have to write but you’re also not allowed to do anything else (so you might as well write something).

I’d like to give that a try and if I can turn it into a habit, I would gladly add it to the collection of tools in my smart process. I’ll update here later with results of this experiment.

Update

I accidentally got to use this advice when I was stuck waiting in a car, having nothing else to do. I thought, “I might as well write,” and I wrote a lot on my phone.

Limiting distractions really does work. I should create opportunities for myself to be stuck somewhere more often.

Lesson 3: Flexibility isn’t evil

In the past, I’ve blamed my long writing lead time on the problem that I change my mind. I create a solid plan, but when writing, I diverge from the plan when I spot an interesting alternative, and this creates a butterfly effect. Everything changes. I end up with more revisions, more rewrites.

When I started my latest project, Soul Seekers, I thought it’s a great opportunity to write out a detailed scene plan and follow it religiously. I didn’t last even two chapters. I found an alternative story to tell and I went for it.

Well, I’ve come to the conclusion that changing my mind isn’t a problem at all. I naturally gravitate towards flexible planning approach, and I think my stories would suffer if I didn’t.

And so the grand lesson is, take full advantage of what approach works for you instead of trying to change it. Flexibility isn’t a hindering, it’s an adaptation method. As new story parameters emerge, adapt. Stay flexible and carry on.

Lesson 4 and 5: Understanding what is an audience and Connecting the dots

A lot has been going on and I think it’s time for an update. I’ve learned a new lesson but I’m still thinking of the best way of phrasing it. I’ll give it some more thought later and will likely override everything I’m writing here right now. I think it has to do with my understanding of my own conclusions. I keep going back to this phenomenon when I get a realization about a topic and then I realize that I had actually figured it out long before, but I simply had not known what I had figured out. Maybe it’s the case of not being ready to learn the lesson. Hmmm.

I’ve written all this out and it turned quite long. Oh, dear. I think it deserves its own post—coming soon. I’m still digesting it all, but for now, here’s the summary of my two major takeaways:

- I’ve been looking at the term “audience” wrong in the past. It’s not about demographics. It’s about how my perfect audience finds my work. How do they consume it? What appeals to them? Where do they find it? That’s what I need to focus on whenever I think about the audience.

- Connect the dots. Sometimes solutions hide in plain sight. Sometimes I already know the answer, but I haven’t asked the right question.

While the first lesson is self-explanatory, the second one needs work. I feel like I’m onto something, I just haven’t figured out what yet. I’ll update once I get my thoughts better organized.

Lesson 6: Choose the right tool for the job

May has rolled around and I’ve had some new insights.

When I started writing Soul Seekers recently, I used the opportunity of a new project to write down the steps I was taking and pay attention to what works, what doesn’t, and what’s redundant. I’m starting to come to certain conclusions that I don’t necessarily like. But that’s good. Learning what not to do is helpful in becoming more efficient.

Let’s start from good news.

1. I’ve become better at planning.

While I still fell into the trap of planning one thing but writing the other, my planning process was fairly smooth and efficient. When I changed my mind about some details of the story, I had to redo my plans, but it wasn’t extremely painful. It definitely helped that this is a simple story.

2. I’ve locked down what planning structure works for me

I’m a huge fan of Story Grid and follow Shawn Coyne’s advice a lot, but I’ve made certain adaptations to Story Grid methodology for my own use, the biggest of which is in sequences. Since this is my natural way of writing, I’m going all in, embracing the magic of sequences. They’re now at the core of my planning, writing, and editing. Sequences rule!

3. Cutting my losses

This was a painful realization to come to, but I found that I was yet again keeping notes in multiple places which made them quickly outdated and inaccurate because I would update them in one place but not the other. Something needs to give so I looked at what I’m getting more value from for my time.

Where am I keeping story planning notes right now? Two major places: Google Sheets and Campfire. Ever since I started using Campfire, I’ve wanted to move all of my planning processes to it. I’ve invested a lot of time and energy to try to make it work, but I continuously find myself unable to do what I need to do. I keep returning to Sheets. At least in Sheets I have control. I can use my skills to customize things and make them as awesome as I imagine them.

This isn’t a permanent decision. If I find a better way to plan within the app or if Campfire team wows me with an update that solves the major issues I’ve encountered, I may return to full-on planning in there. Also important to note that I am absolutely not abandoning Campfire. It is still my main project organization tool and that’s where I write my books. I’m just not going to try to plan them in there anymore for the time being.

Update: I have found how to visually represent my story within Campfire by using the Maps module. Ha! I bet you didn’t see that coming? I certainly didn’t. I’ll write a blog post about it (hopefully soon).

Back to Lesson 5: What connecting the dots actually is

While revisiting The Gathering recently, I had several Aha! moments of editing win. This is the type of an edit that fixes a scene that previously lacked an element that now seems obvious. The scene’s actual meaning and actual role hid under a blanket of inexperienced writing, a blanket I was only able to unveil after enough time passed.

When that type of a fix happens, I’m always pleasantly surprised, but also frustrated because I’m never quite sure how I did it. If you asked me to explain, I could probably follow the logical path that led me there, but I haven’t noticed a distinguishable pattern that would teach me how to do it again and fix every scene, solve every problem. How do I capture the magic of the Aha! moment?

And it dawned on me that it’s a matter of instinct and trust.

When reading back an old scene, sometimes I can feel in the back of my mind that something is off. This off feeling is always so subtle, that it’s way too easy to ignore or rationalize. Only with the repetition of reading back/listening to the same scene in the cycle of editing, do I really notice it. I get the deja vu of “I’ve had this thought before” variety. And then I fix the scene, and suddenly, it becomes obvious what was triggering my spidey senses.

As for trust, this has to do with “there was a purpose to this scene” variety. When editing, it is so easy to look at a scene that doesn’t work and just say, well, maybe I don’t need this at all? Maybe I should cut this? In practice, I found that I’m reminded of why I had written the scene in the first place only after I’ve edited it.

And yes, sometimes, a scene might have to be cut maybe because it doesn’t work with the story or contradicts the plot, or maybe it drags the story down (I have once cut down two chapters into one paragraph summary), but that shouldn’t be the first reaction to an imperfect scene. Sometimes, all it needs is a little redirection, or to dig deeper, or to look at it from the point of view of the finished story. At the time of writing the first draft, I instinctively knew that I needed this moment but did not know what the reason was just yet.

New process: My big picture takeaway from that lesson is to trust myself and listen to my instincts, even if they’re very faint. And reread/relisten until my spidey senses are blissfully calm.

Lesson 7. A sense of mystery

This relates to lesson 5, but it was a big Aha! moment in general so it deserves its spotlight.

I was revising the beginning of Soul Seekers, and got the first chapters to where I wanted them to be in terms of content but something was still missing. I feared that the first chapter’s hook was weak and racked my brain how to improve it. It’s a cool story, and I want the readers to feel that from the beginning. But how?

Meanwhile, in an unrelated note, I had landed on a book called Into the Light only because I liked the cover (the color scheme and the style fits with what I’ve been doing for my series). The Amazon blurb wasn’t very clear about the story (not the best pitch out there), but I got curious enough to peek inside. I get curious sometimes about published books. I want to know why they were published. Are they any good? What are these authors doing that I’m not?

And so I’m reading the first page. And at first, I wasn’t impressed. I could write that. But before I even got to the end of the page, I noticed that I was interested.

It was a simple set up. A guy walks into a diner, orders food, and wants to watch the local TV while waiting. I found that I wanted to know why he was so determined to watch the local TV or why it appeared that he knew the guy on the screen. Who was he in relation to the protagonist?

And so, I barely read a page or two and I already had all these questions about what was going on, and that was when it hit me. That is how you do a hook. You make the readers ask themselves a question, and you hold back the answer a bit. For every answer you give, more questions should be introduced.

Okay, so this shouldn’t have come as surprise. Adding a sense of mystery is a common piece of writing advice, but there’s a difference in hearing advice and being able to see an example of it to put to the test. Or maybe it was a case of the right place and time. Maybe I wasn’t ready to understand this advice before.

In any case, I went back to my first chapter and looked for opportunities of where a reader could pose a question. I pulled back wherever the answer was given too fast, and I added tiny details that hopefully will make the readers wonder why that detail is there. And I think I’ve finally fixed it.

New essential process: Scan your first chapter for exposition. Rewrite it so instead of serving the answers on a boring silver platter, allow the readers to suspect that there is an answer out there and if they keep reading, they’ll find out what it is. Tease them. Don’t give them what they want. Not until later.

Lesson 8. My grand list of writing advice

As the year is slowly winding down, I reflect on what I’ve accomplished this year. I wrote a new book, Soul Seekers (sequel to Soul Survivor). I edited Soul Survivor well enough to get it ready for publishing (more on that soon). I’ve also gotten quite a lot of ideas recently how to edit and continue the TriRealm Trilogy. Things are looking up writing-wise.

I’ve also gotten back to the once-abandoned hobby of drawing. I’ve already improved a lot and I hope that with practice, I might actually be okay at it.

What is the lesson learned from all of that? Perhaps something about courage and persistency? Maybe we’re going back to one of the previous lessons: trust yourself. I think I trust myself a lot more nowadays. I don’t get swayed by doubt and fear as much.

But since I have accomplished those points, then I’ve done something right. Perhaps the lessons learned were not in vain. So how can I incorporate them into my future writing processes? Let’s summarize what we’ve got so far.

- Recognize when the core moments are unsatisfactory and innovate the scene idea. Do not settle for “good enough.” Trust yourself when you feel that it’s not good, and challenge yourself to innovate the idea until you land on one that excites you.

- Limiting distractions really does work. I should create opportunities for myself to get stuck somewhere more often so I have no choice but to write.

- Take full advantage of what approach works for you instead of trying to change it. Flexibility isn’t a hindering, it’s an adaptation method. As new story parameters emerge, adapt. Stay flexible and carry on.

- My “audience” is not defined by demographics. It’s about how my perfect audience finds my work. How do they consume it? What appeals to them? That’s what I need to focus on.

- When examining your writing process, pay attention to what works, what doesn’t, and what’s redundant. Cut your losses where you must.

- I must trust myself and listen to my instincts, even if they’re very faint. And reread/relisten until my spidey senses are blissfully calm.

- Scan your first chapter for exposition. Rewrite it so instead of serving the answers on a boring silver platter, allow the readers to suspect that there is an answer out there and if they keep reading, they’ll find out what it is. Tease them. Don’t give them what they want. Not until later.

Nice list. The year is far from over. Let’s see if we can add more to it.

Conclusions

This has been quite a year. I got a lot done. I published my first book at last (Soul Survivor – more on that here). I’ve also gained more confidence as a writer. I feel that I know the craft well enough to write books efficiently. Is my process perfect? Absolutely not, and I suspect that it will continue to evolve over my lifetime, but I feel like this year’s goal has been achieved. I tried out new things and learned a lot. Now I’m ready to step forward to the next adventure: publishing.

See ya next year.

Discover more from Isobel Lynx

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.